You stand in Stratford-upon-Avon on a February morning, mist clinging to the Avon, and you're holding a coffee that's too hot and thinking about the weight of names. How many Stratfords are there now? Connecticut has one. So does Texas. Ontario claims another. All of them named after this place: this specific bend in a river where a glover's son learned to write plays that made the language bend too.

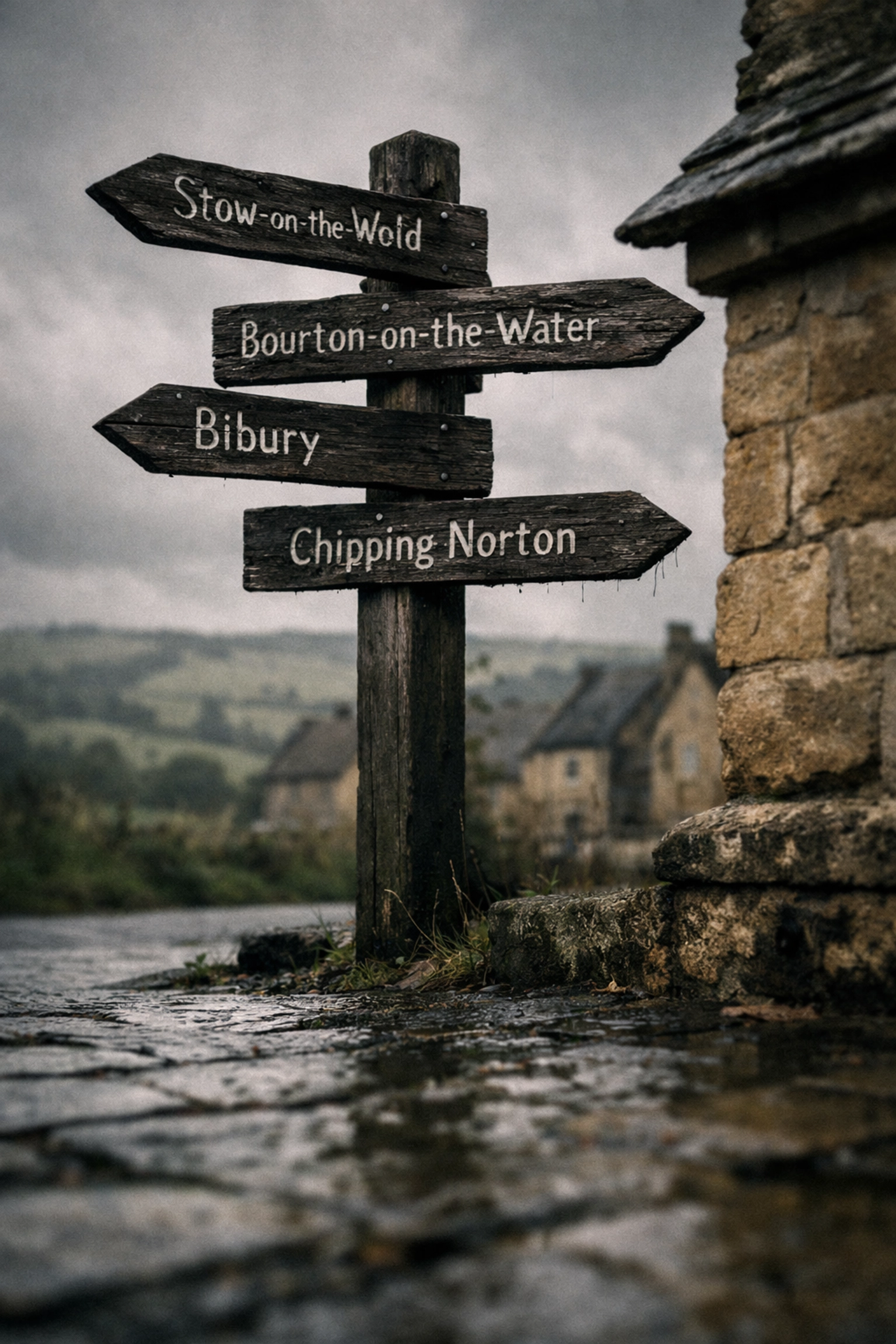

Names are cargo. They cross oceans in the holds of ships, packed tight with homesickness and ambition and the need to plant something familiar in unfamiliar soil. The Cotswolds: along with Bath, Canterbury, Dover: these weren't just places the English left behind. They were coordinates on a map of memory, carried west and hammered into signposts across a continent that had its own names long before any European drew a boundary line.

This isn't about tourism. It's about what people take with them when they leave, and what they try to rebuild when they arrive.

Stratford: The Weight of a River and a Name

Stratford-upon-Avon isn't difficult to decode if you know your Old English. Stræt means road: specifically a Roman road. Ford means exactly what you think it means. This was the place you could cross the Avon where the road met the water. Functional. Practical. No poetry required.

But Shakespeare changed that. The name became exportable not because of the river crossing but because of the man who was born beside it. By the time Puritan settlers were naming towns in Connecticut in the 1630s, Shakespeare was already a ghost they couldn't shake. Stratford, Connecticut went up in 1639. The settlers wanted a piece of that legacy: or at least the illusion of it.

Stand on Clopton Bridge here in the original and you can feel it. The Avon moves slow and brown beneath you, the Royal Shakespeare Theatre squats on the far bank, and the whole town hums with the business of being someone's birthplace. It's commerce now. It was commerce then too, just different currency. The name traveled because it carried weight: cultural, literary, aspirational. A way to say we came from somewhere that mattered.

When you roll through on one of our Cotswolds tours, you're seeing the source code. The original. Every other Stratford is a photocopy.

Bath: Thermal Memory Exported

Bath doesn't need explanation. The Romans built Aquae Sulis here because the hot springs bubbled up at 46 degrees Celsius and wouldn't stop. Healing water. Sacred water. Water that made a city possible. The name is simple: Bath. You go there to bathe. The Georgians turned it into high society, but the springs were doing their work long before anyone built a Pump Room or a Royal Crescent.

Bath, Maine got its name in 1781. Bath, North Carolina came earlier: 1705. Neither has hot springs. What they had were rivers and a need to sound like they came from somewhere refined. Bath wasn't just a name by then: it was a brand. It meant elegance, health, European sophistication. The American towns were borrowing aspiration, not geography.

You can visit the Roman Baths in the English original and stand on ancient stone, looking down at water that's been rising for ten thousand years. The steam curls up. It smells faintly of minerals and time. This is what those American towns wanted to reference: this sense of deep history, of something older than the colonial project itself. They couldn't take the water, but they could take the name.

Our Bath and Stonehenge tour drops you into that history. You walk the same stone. You see the same green water. You understand why the name had power.

Stow-on-the-Wold: A Village That Traveled in Fragments

Stow-on-the-Wold sits high: the highest town in the Cotswolds at about 800 feet. The wool trade built it. The market square could hold 20,000 sheep on fair days. Stow means meeting place. Wold means upland. Put it together and you get a practical description of a place where deals were made and fortunes were spun from lanolin and fleece.

There's a Stow in Massachusetts: settled in the 1680s. There's another in Ohio. Both dropped the poetic suffix, kept the core. Stow was enough. They weren't trying to rebuild the wool market. They were claiming the name of a place that meant commerce, centrality, survival on high ground.

Stand in the market square in the Cotswold original on a quiet morning and you can still feel the echo of all that activity. The King's Arms sits on one side, golden stone glowing. The alleyways: called "tures": run tight between buildings, designed to funnel sheep toward the square. It's all function dressed up as charm now, but the bones are trade.

The name crossed the Atlantic because it was memorable and because it suggested prosperity. A place where things happened. Where you could build something. Where the ground was good.

Camden: The Merchant's Mark

Chipping Campden is one of those Cotswold villages that looks like someone designed it to sell tea towels. Honey-colored limestone. Thatched roofs. The High Street runs straight and perfect, lined with buildings that date back to the wool boom of the 14th and 15th centuries. Chipping comes from ceapen: an Old English word for market. Campden was a valley. Market in the valley. Another functional name that became beautiful by accident.

Camden, New Jersey came later: 1773. Camden, South Carolina followed. Both shortened the name, dropped the market reference, kept the core sound. The connection isn't exact, but the pattern holds. English place names carried the weight of legitimacy. They said this isn't wilderness: this is civilization, transplanted.

Walk down Campden's High Street and you're walking through preserved wealth. The wool merchants built these houses to last and to impress. St. James' Church anchors one end. The Market Hall sits in the middle, built in 1627. The whole village is a monument to what happens when trade routes favor a place long enough for people to build in stone.

The American towns took the name but couldn't take the context. They built their own. Different industries. Different fortunes. But the name was a tether back to something old, something proven.

Canterbury and Dover: Gateway Names

Canterbury and Dover aren't Cotswolds: they're Kent, which we cover on another route: but they complete the picture because they were gateway names. Ports and pilgrimage. Arrival and departure. Canterbury meant religion, history, Chaucer, murder in the cathedral. Dover meant white cliffs and the last sight of England before the crossing to France.

There's a Canterbury in Connecticut: 1703. Dover is everywhere. Delaware, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Ohio. The list goes on. These were names that carried symbolic weight. They weren't just places: they were concepts. Canterbury was faith. Dover was threshold.

Stand at Dover's cliffs and you're looking at the edge of something. The Channel churns below. The chalk rises white and stark. This was the view that launched a thousand ships and a thousand emigrations. When colonists named their new towns Dover, they were planting a marker that said we crossed from there to here, and we're still English.

Why They Carried the Names

Homesickness is part of it, but not all of it. Names were tools of empire: soft power before anyone called it that. They anglicized the landscape. They overwrote indigenous names with English ones, creating a linguistic map that pointed back to the mother country. It was about control, memory, and the assertion that this place: wherever it was: was an extension of that place.

But there's also something more human in it. When you're standing in a forest in Massachusetts in 1680 and everything smells wrong and sounds wrong and the winter is colder than anything you knew in Gloucestershire, naming your settlement Stow is a kind of prayer. It's a way to say I haven't forgotten. I'm still from somewhere.

The names were ballast. They kept people tethered to an idea of home even as they built something entirely new. And in the act of borrowing, they created echoes: dozens of Stratfords, Baths, Dovers, each one a ghost of the original, each one its own place now with its own history.

What It Means Now

When you visit the English originals: Stratford, Bath, the Cotswold villages: you're not just seeing picturesque architecture and rolling hills. You're seeing the source material. The places that were so fixed in the imaginations of emigrants that they rebuilt them, in name if not in stone, across an ocean.

We run tours that put you in these specific places. Small groups. Sixteen seats. No megaphone guide shouting over engine noise. You get time to stand in the market square in Stow-on-the-Wold or walk the Roman Baths in Bath and feel the weight of what these names carried.

Because that's what travel is supposed to do. Not just show you something pretty: though the Cotswolds delivers that: but connect you to the layers underneath. The history. The trade routes. The migrations. The reasons a name mattered enough to pack it in a trunk and carry it three thousand miles to a place that had never heard of wool merchants or Roman springs or a glover's son who wrote plays.

You stand in these places and you understand: the map wasn't just redrawn. It was folded, carried, and unfolded again. And the names( they stuck.)